What Stories Reveal About Oppression

It's easy to ask why stories are important when you're free to tell any that you like. When only one story is allowed, the value of storytelling becomes clear.

Few books can grab attention in the author’s note, but Azar Nafisi pulls it off in Reading Lolita in Tehran:

“Aspects of characters and events in this story have been changed mainly to protect individuals, not just from the eye of the censor but also from those who read such narratives to discover who’s who and who did what to whom, thriving on and filling their own emptiness through others’ secrets.”

That’s only the first half, and it’s an arresting indictment of those who misuse stories.

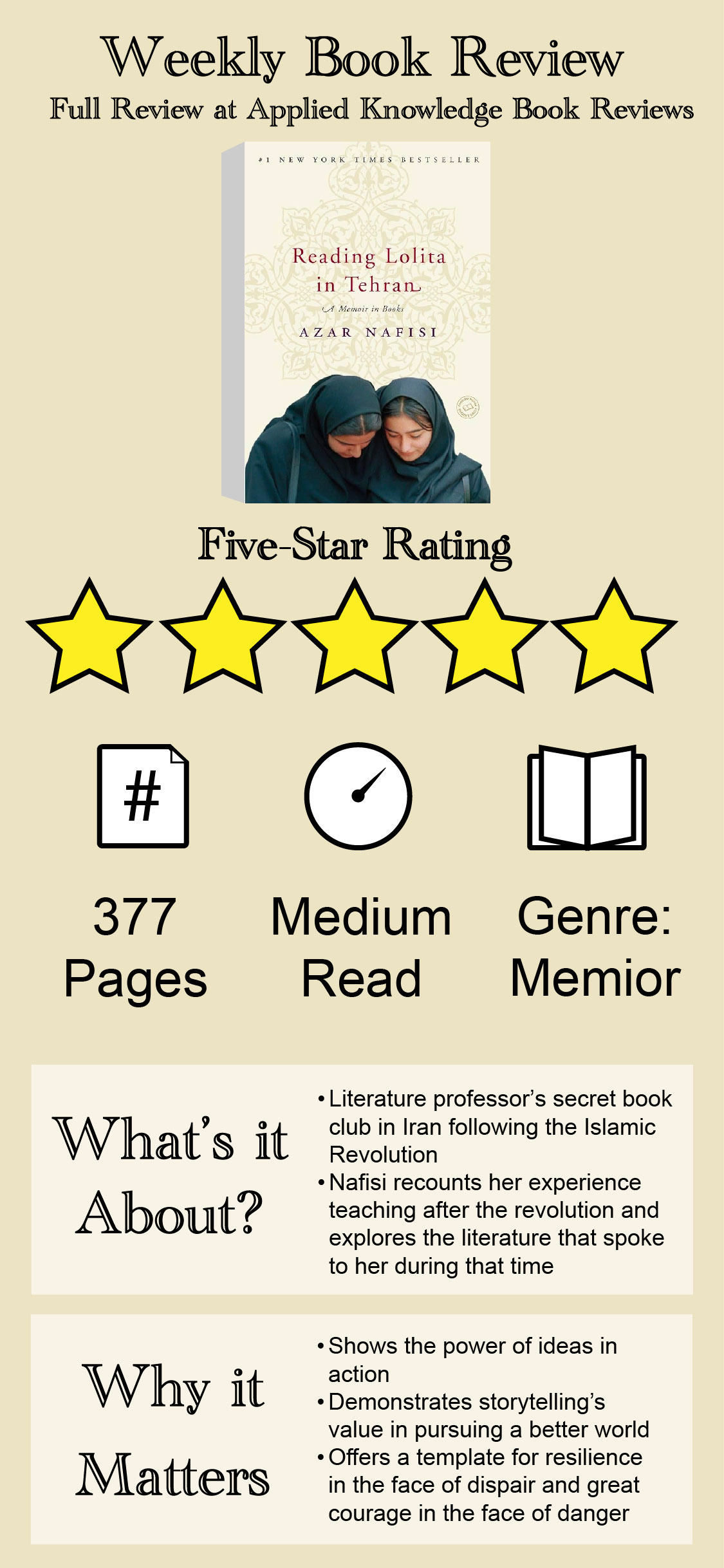

Azar Nafisi was a professor of literature in Iran before and after the Islamic Revolution. As the rights of all Iranians evaporated around her, Nafisi found refuge in reading and teaching literature.

Her ongoing act of defiance was a secret book club held with seven students - six women, one man. Even after she resigned from the university, she continued this book club, helping all of her students through the consequences of the Revolution.

The books they studied weren’t just for fun or comfort, either. Nafisi’s picks revealed the building blocks of the new repressive government more clearly than some journalism could.

Lolita Is About Life Lost, Not Just a Child Predator

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov is a beautifully written story of a nauseating crime. It’s told from the perspective of Humbert Humbert, a pedophile who becomes the stepfather and then sole guardian of a pre-pubescent girl named Dolores Haze. Humbert calls her Lolita.

The resonance this story had with a group of Iranian women after the Revolution may surprise readers at first. One of the book club’s women, Yassi, moved from her hometown to Tehran to attend university. She also refused to marry and still didn’t want to when Nafisi asked her to attend the book club.

Nafisi told Yassi that in many of Nabakov’s novels, “there was always the shadow of another world, one that was only attainable through fiction.” In the case of Lolita:

“This was the story of a twelve-year-old girl who had nowhere to go. Humbert had tried to turn her into his fantasy, into his dead love, and he had destroyed her. The desperate truth of Lolita’s story is not the rape of a twelve-year-old by a dirty old man but the confiscation of one individual’s life by another. We don’t know what Lolita would have become if Humbert had not engulfed her. Yet the novel, the finished work, is hopeful, beautiful even, a defense not just of beauty but of life, ordinary everyday life, all the normal pleasures that Lolita, like Yassi was deprived of.”

The isolation that Lolita feels throughout the story is so powerful that even Humbert acknowledges it. Her isolation also resonated with Nafisi and Yassi, whose lives were tightly bound by the Islamists in power. Nafisi points out that even holding hands with a partner in public could lead to arrest by the new morality police. Substantial parts of their private lives had been captured.

Mediocre Men Were Newly Empowered

Five pages after Nafisi explained Lolita’s resonance, she mentions a note she made about one of the early book club meetings:

“Some of my girls are more radical than I am in their resentment of men. All of them want to be independent. They think they cannot find men equal to them. They think they have grown and matured, but men in their lives have not, they have not bothered to think.”

During one book club meeting, Sanaz was late. She’d missed a couple of meetings, and no one had thought anything of it. They knew that Sanaz had been on vacation with some friends.

What they didn’t know was that Sanaz and her five female friends were hanging out with a male friend in a villa on the Caspian Sea. The morality squads caught them and the women were arrested.

Their two nights in jail included two visits to clinics for virginity tests. At the first one, a group of medical students observed the procedure. The second procedure was because the guards “were not satisfied with her [the female gynecologist’s] verdict.”

The womens’ parents finally found them on the third day. Afterward, the women “were given a summary trial, forced to sign a document confessing to sins they had not committed and subjected to twenty-five lashes.”

These men weren’t just out in society. Sanaz’s younger brother sided with the morality police:

“What did they expect? How could they let six unruly girls go on a trip without male supervision? Would nobody ever listen to him, just becasue he was a few years younger than his scatterbrained sister, who should have been married by now?”

Sanaz’s brother had driven her to that book club meeting. She could no longer use her car and was now “being chaperoned by [her] wise younger brother.”

People Who Don’t Have to Think Rarely Make the Effort

While many women were contending with dangers like the one Sanaz endured, many of the men were enforcing the new rule. It’s no wonder several of the women in Nafisi’s book club felt like they couldn’t meet men their equal. When right and wrong were decided by the clerical government, the men didn’t have to put in the same effort as women in to develop character or self-actualize.

That’s not to say all the men suddenly viewed women the way that Sanaz’s brother did. Nafisi recounts a male coworker who continued to speak to her the way he did before the Revolution. However, he refused to make eye contact with her. At this point, men were forbidden from making eye contact with the women they worked with.

He may not have supported that policy, but he knew what could happen to him if the morality squads caught him violating these new rules.

The Blind Censor and Iran’s New Reality

Early in her book, Nafisi introduces the blind censor. He was Iran’s chief film censor until 1994. He started as a theatre censor who decided which parts of plays to censor based on his assistant’s descriptions of the play.

When he moved on to censoring film, scriptwriters would send him scripts on audiotape.

“He then made his judgments about the scripts based on the tapes. More interesting, however, is the fact that his successor, who was not blind - not physically, that is - nonetheless followed the same system.”

It’s a haunting image of a small group of men shaping the lives of an entire country, following one another more closely than the consequences of their actions. Nafisi often found that all she could offer her students was an escape through fiction. Literature became a temporary refuge where her students’ experiences could be seen and where for a few hours per week, they shaped worlds of their own.