Why Financial Markets Have Large Booms and Busts

Financial markets are more unstable than the Efficient Market Hypothesis would have you believe. There's another theory that better explains market irrationality.

Economic crises are complicated, so it’s natural to turn to experts to explain how the crisis happened and how to manage it. Unfortunately, some of those experts are pundits repeating talking points instead of grappling with data.

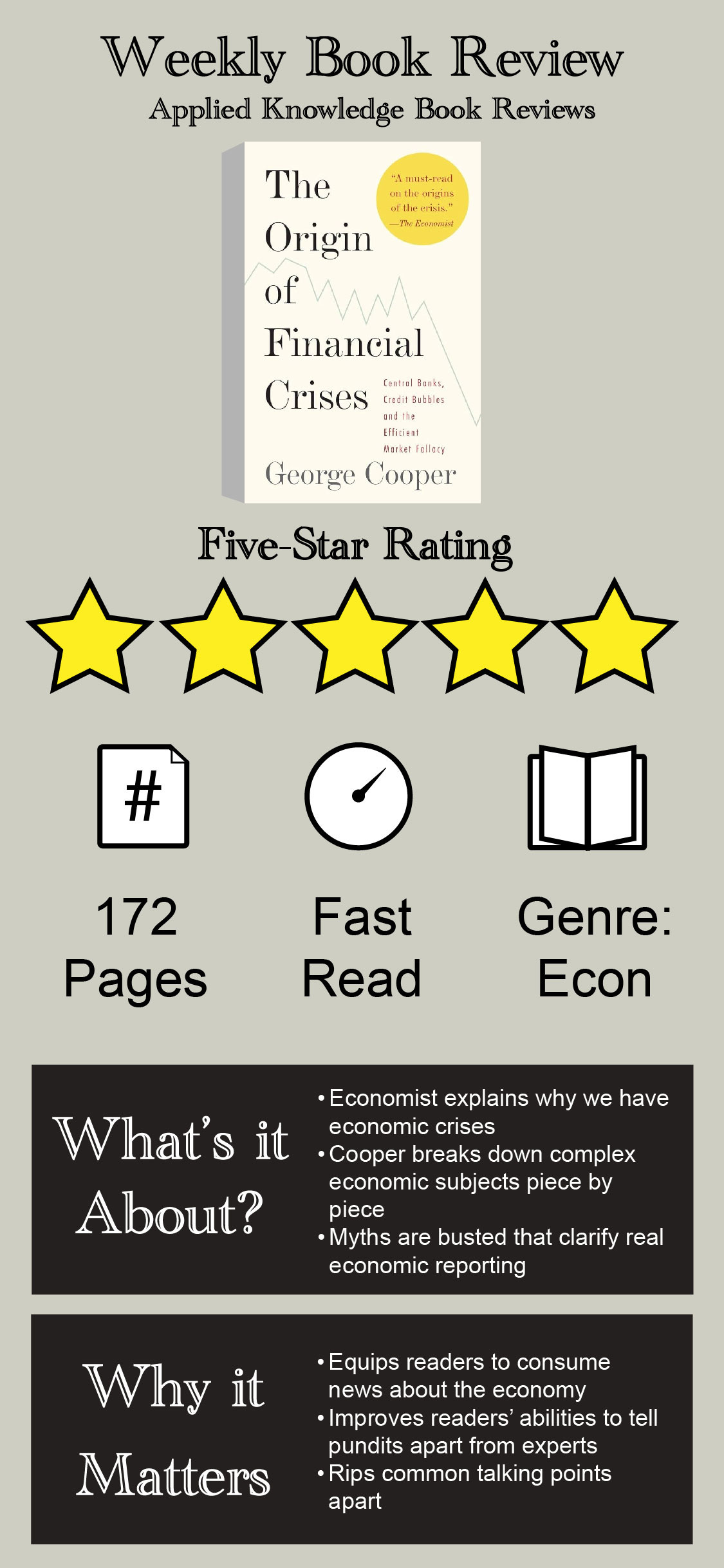

The Origin of Financial Crises is George Cooper’s explanation of how economic systems become unstable and why it takes more than an efficient market to manage severe crashes.

Some of the information in this book is technical, so it’s not a gentle introduction to economics. However, the text is plain-spoken enough that anyone willing to google a few terms or who’s willing to re-read a few pages can draw the most valuable ideas from it.

One of the most valuable ideas is a theory that adds much-needed nuance to economic conversations.

Why Financial Markets Have Large Booms and Busts

You may remember the law of supply and demand from high school economics. If a baker has a high demand for bread, he’ll increase the price of bread. If his customers suddenly decide to go keto, the baker will have a higher bread supply than demand, and his price will decrease. Price finds an equilibrium between supply and demand.

In markets for products, businesses respond to pressures outside of their businesses, like how many people want their products and whether that business’ supply chain can meet customer demand.

However, financial markets are different. Financial asset prices get pushed around by forces internal to financial businesses. Cooper explains early in his book:

“Two internally-generated destabilising forces have already been introduced in the form of: supply, or the lack therof, as a driver of demand in asset markets; and asset price changes as a driver of asset demand.”

In a bakery, the supply of bread doesn’t lead to more demand for bread. A baker could bake a city’s worth of bread, but customers aren’t going to buy it all just because it’s available.

But on a stock exchange, a low supply of stock causes increased demand for it. When a company buys its own stock back, that company can increase its earnings-per-share, making the stock more valuable.

Consequently, traders want to hold that stock. Traders will buy more of it, which increases the price further. Other traders hoping to ride the wave from a lower price to a higher one buy in, too. If an asset’s price gets too high, it can result in a bubble waiting to pop.

“Frequently in asset markets, demand does not stimulate supply, rather a lack of supply stimulates demand,” Cooper wrote. “Equally price rises can signal a lack of supply thereby generating additional demand, or, conversely, price falls can signal a glut of supply triggering reduced demand.”

The supply and demand model still holds true in asset markets as it does in product markets. However, the Efficient Market Hypothesis doesn’t account for the way that supply directly impacts demand in asset markets.

Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis does.

How Minsky’s Instability Hypothesis Adds Nuance to Efficient Market Theory

In a product market, prices move to balance supply and demand caused by customers, supply chains, and forces outside the business. Cooper explains Hyman Minsky’s theory for financial markets:

“By contrast, Minsky’s Instability Hypothesis argues that financial markets can generate their own internal forces, causing waves of credit expansion and asset inflation followed by waves of credit contraction and asset deflation.”

Think about the 2008 financial crisis, when this book was written. Homes had been overvalued because of investments that could be packaged and sold outside of public stock exchanges. These investments pushed the prices for homes higher until the bubble popped.

When enough panicked investors sold their investments, the prices of those investments and the assets they were tied to dropped, too. The chain of loans that funded those investments meant that not only investors lost money. Many financial institutions lost money too — enough for some banks to close and further panic consumers.

A theory that predicts how crises like these work would inform better economic policy to soften the next panic-induced recession. However, central banks are caught between two competing goals, complicating their future responses.

Central Banks: What They Do and What They Argue About

Central banks have two jobs: maintain price stability and avoid or soften recessions. They’re noble goals. Price stability ensures that money remains valuable, and preventing or softening recessions offer relief from the hellscape of layoffs and financial hardship.

But there’s a problem: pursuing one goal undermines the other.

Central banks can encourage economic growth by lowering interest rates.

“However,” Cooper wrote, “as the stock of debt rises the central bank eventually reaches a point whereby lowering interest rates is not sufficient to encourage more private sector borrowing; private sector lenders refuse to pass on the central banks lower interest rates, and anyway, borrowers become concerned over their ability to pay off their stock of debt as well as their ability to meet interest payments.”

At that point, lowering interest rates to encourage borrowing does little. Consumers need their money to pay down debt instead of buying new things. Lower spending can risk a recession, and if the central bank wanted to maintain price stability, it could allow the recession to occur. Cooper has a counterargument for that approach:

“Allowing an economy to free fall into recession from a point of extreme over-indebtedness is extremely dangerous, risking a self-reinforcing economic collapse along the lines of that which happened in the Great Depression. The alternative is to simply pay off the debt through the printing press. Quite simply the government prints itself more money. It may then spend that money to generate inflation, to make the debt less burdensome, and it may even give som of the printed money to those that are indebted. But of course this inflationary “get out of jail card” requires the central bank to discard its new role of guardian of price stability.”

Printing money — in moderation — causes inflation but can relieve the economic struggles of a country’s citizens. Failing to relieve those struggles can allow a recession to begin or worsen. But over-printing can lead to inflation that creates new economic hardships, which could be countered with stimulus packages, which could lead to higher infla…

The arguments can circle endlessly. Going in those circles is a favored tactic of TV economists. But the nuance lies in the details of the present economy and which tradeoffs are most necessary.

Anyone who wants an introduction to any of these issues will enjoy George Cooper’s short work on financial markets, the role of central banks, and managing an economy without abandoning capitalism. It’s a clarifying look at financial crises that is best read during times of peace before the emotions of the next crisis cloud judgment.