What Makes Even Experts Make Poor Judgments

Noise is the kind of information that diverts people from making their best decisions. It can also be harder to fix than bias.

There are a few ways to make better decisions, but a lot of the focus is on bias. Bias is just being wrong in the same direction over and over again. One of the most common is political bias that comes from reading the same sources for political analysis instead of checking it against critics with different values and policy priorities.

However, there’s a source of mistakes that demands greater attention: noise.

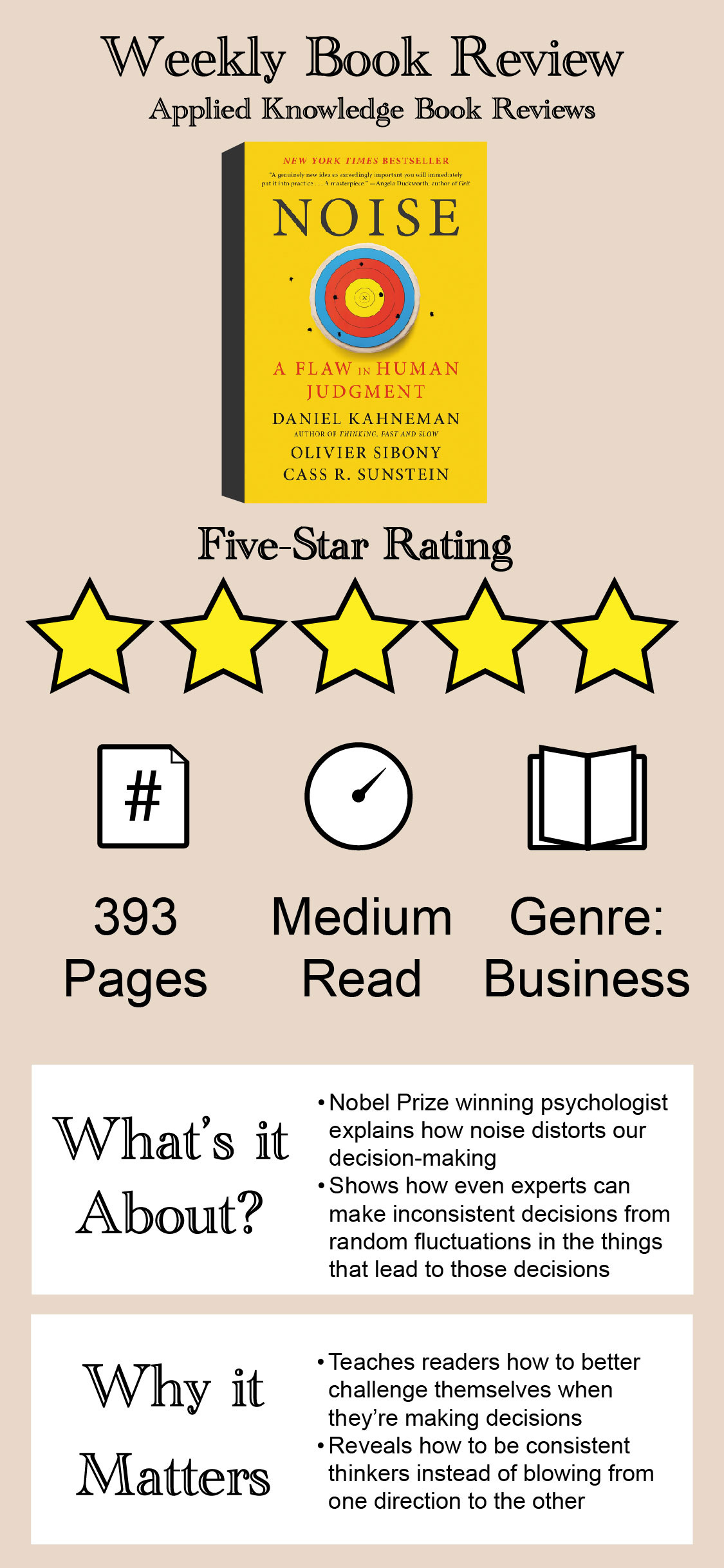

Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass Sunstein define noise as “variability in judgments that should be identical.” Their book, appropriately titled Noise, works through the ways that noise distorts the information we use to make decisions and how we can eliminate it. An early quote from the book is a good summary of what good decision-making looks like:

“Good decision making must be based on objective and accurate predictive judgments that are completely unaffected by hopes and fears, or by preferences and values.”

Why Noise and Bias are Different

To be right more often, decision-makers need to eliminate two sources of error: noise and bias. A lot of people use these terms interchangeably, but fixing one doesn’t necessarily fix the other.

“In terms of overall error, noise and bias are independent: the benefit of reducing noise is the same, regardless of the amount of bias.”

For example, an insurance company could pay too much attention to a patient’s age when deciding how much to charge them for coverage. Caring about age over other health factors would be an example of bias. Factoring in unrelated factors like job satisfaction or a customer’s astrological sign would add noise to coverage decisions.

If you could wave a magic wand and reduce noise, you would make all your decisions more similar, but you would immediately see any bias in your decisions. Reducing bias could broaden the range of decisions you make, but you wouldn’t necessarily be more accurate.

Even using a group to narrow decisions down doesn’t eliminate these issues. As Kahneman and company write:

“The reason [groups are imperfect judges] is basic statistics: averaging several independent judgments (or measurements) yields a new judgment, which is less noisy, albeit not less biased, than the individual judgments.”

A group can come together to produce an answer to a problem, but if all of them believe similar things, they’ll miss the mistakes they have in common, and there will be little benefit to a less noisy decision.

This insight leads to an important caveat about harnessing the wisdom of crowds to make decisions.

Wise Crowds have Conditions

Business reporter and professor James Surowiecki wrote a book called The Wisdom of Crowds that explains the conditions that make crowds wise. One of those conditions is independence, and Kahneman seizes on its importance for Noise:

“…independence is a prerequisite for the wisdom of crowds. If people are not making their own judgments and are relying instead on what other people think, crowds might not be so wise after all.”

Wise crowds are powerful, but they can be vulnerable to herding. Herding is when members of a group choose to agree with other members instead of bringing their independent assessments to the group.

“The irony is that while multiple independent opinions, properly aggregated, can be strikingly accurate, even a little social influence can produce a kind of herding that undermines the wisdom of crowds.”

The important thing to consider when making any decision is how much error is being shaved off with each consideration. Whether it’s a group or individual choice, you have to find ways to ask questions you haven’t considered and fill in gaps in your thinking.

Noise is a great read for anyone who wants to understand why they — or your bosses — make fuzzy decisions sometimes. The book is a great exploration of the way we think, so anyone interested in psychology will get a lot out of Noise, too.