This is How to Write Convincingly

A former New York Times op-ed editor explains how to put a persuasive piece of writing together.

Whether we like it or not, we’re all writers now.

The endless emails, the social media posts, even our texts have turned us into writers. Consequently, we all have to learn how to get our points across in writing, even if we’re not professional opinion writers.

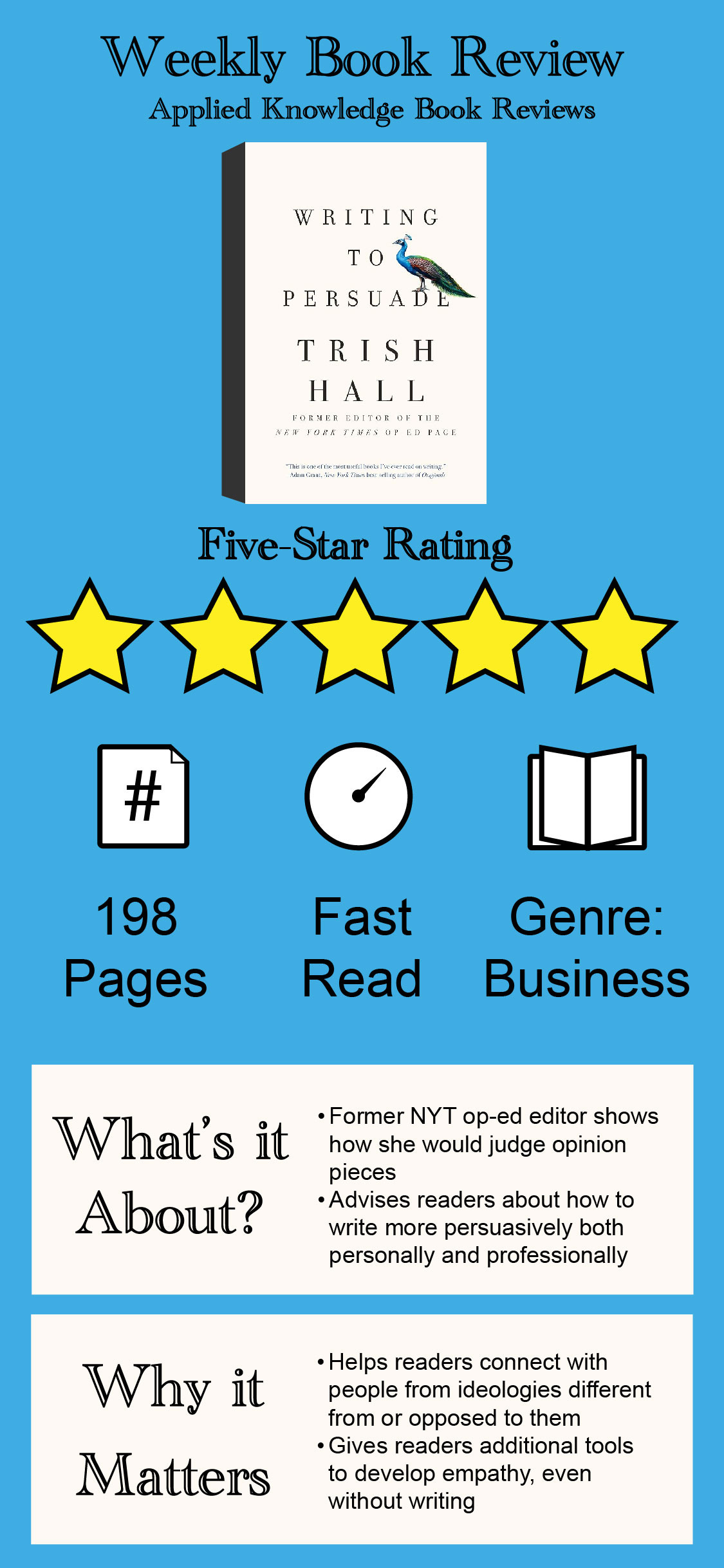

Former New York Times editor of the op-ed page, Trish Hall, wrote a short book, Writing to Persuade. It’s not only an inside look at judging opinion pieces for one of the most well-known newspapers in the world, but it’s also a crash-course on how to persuade people with writing.

There are a few tips that may be obvious. Hall remembers another editor who weighed in on a debate Hall and another colleague were having over which essays to run:

“It has to be a surprising idea or a surprising person writing. If you don’t have either, it’s not worth running.”

The element of surprise is crucial for snapping people out of their pre-conceived notions of what they expect the argument to be. Surprise creates space for new ideas.

There are less obvious tips, too, like conceding points to the other side.

Tell Your Enemy They’re Right

About a third of the way through her book, Hall draws an important lesson from Abraham Lincoln during his legal career. She quotes an essay recounting how Lincoln would execute sneak attacks to win his cases:

”In a legal case or a political debate, recalled [fellow attorney] Leonard Swett, Lincoln would concede nonessential points to his opponent, lulling him into a false sense of complacency. ‘But giving away six points and carrying the seventh he carried his case…the whole case hanging on the seventh….Any man who took Lincoln for a simple-minded man would win up with his back in a ditch.’”

A great way to surprise someone on the opposite side of an argument is to tell them how much you agree with them. Not everyone can have a surprising biography for their point of view, but anyone can concede some points to the other side.

Concessions are also a great way to focus your arguments. Op-eds can have low word-count limits, so there’s no room to have the full argument. Instead, you’ll have to focus on the part of your argument that you can make the strongest in the least amount of space.

Facts Only Go so Far

Hall marks the halfway point with an important point about what counts as arguing with a reader. Again, there are obvious points mixed in with important surprises:

”In your writing, don’t indulge in personal attacks, guilt trips, or berating. Another form of arguing, even if it’s done in a calm voice, involves trying to debunk the ideas your audience believes to be true by battering them with facts that appear to demolish their world view. That won’t work. Social science research shows again and again that we are not persuaded by facts, especially when they are presented as part of an argument.”

Insulting the audience is a clear turn-off, but many people are surprised that relying on a litany of facts is unpersuasive.

If everyone could be moved by the same facts, then there would be far less to argue about. Arguments can also come from weighting facts differently. You may care deeply about the size of government while another voter cares about what it can accomplish at different funding levels. Conflicts go far deeper than facts, even if those facts are indisputably true.

Instead, you’ll have to become a master storyteller. If you were at a bar and telling your friend about something that drove you over the edge, then you would include suspense and thoughts and feelings about what happened. You wouldn’t have a bulleted list of points to present on a powerpoint slide.

Persuasive writing demands an ability to see the world through your opponent’s eyes. Hall’s book is a great place to start for anyone who wants to add some bite to their writing and learn some of the surprising lessons of persuasion.