Rationality is More Than a Buzzword

Anyone can invoke rationality to justify their beliefs. Practicing it is another matter, and it's a moral act as much as an intellectual one.

Can you use the stuff you know to make decisions?

According to Steven Pinker’s definition, you’re practicing rationality.

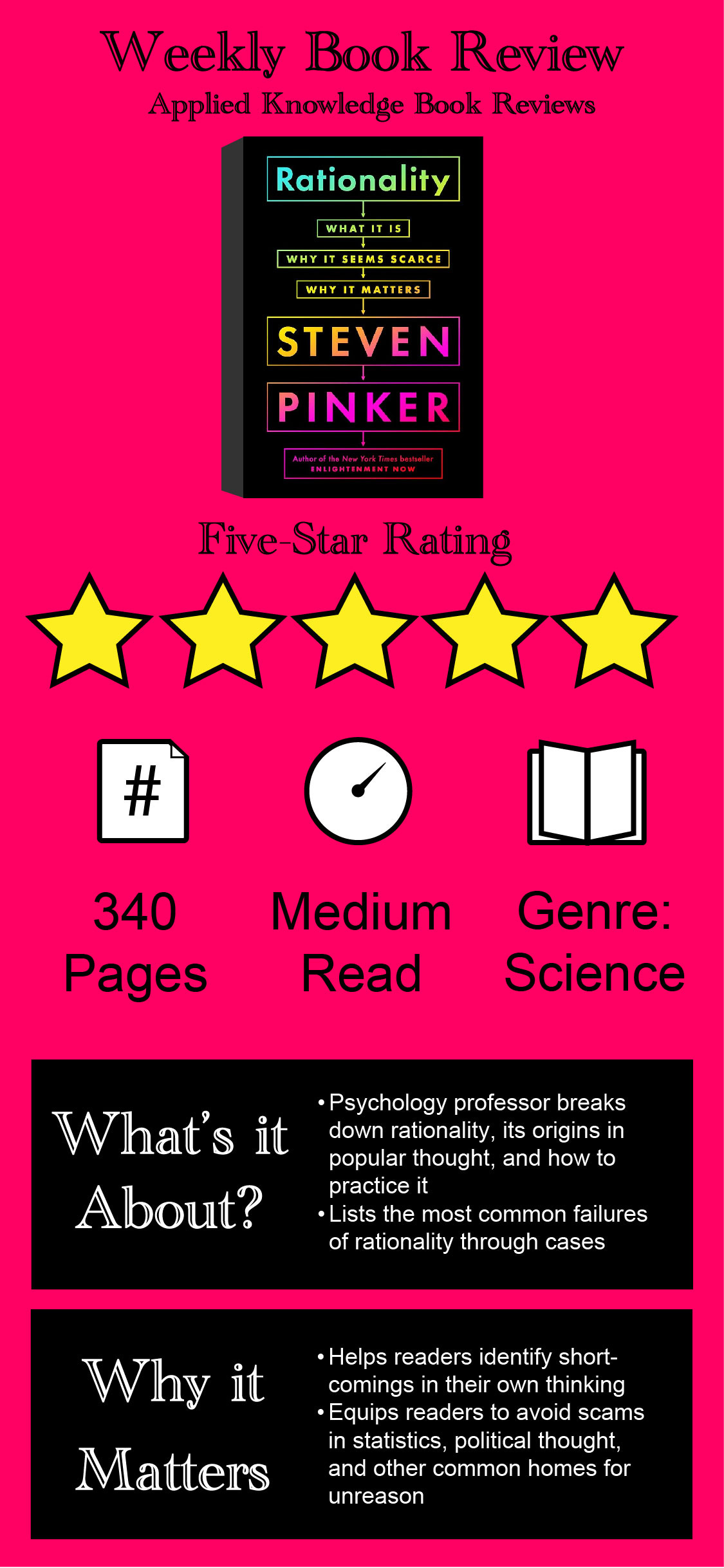

Pinker’s book, Rationality, does more than talk about what rationality is. The book is based on a class that Pinker teaches at Harvard. It breaks down ways that people undermine their own thinking and misinterpret reality.

Rationality also reveals the history of thinkers who elevated rationality above force. During the Enlightenment, those ideas were fleshed out in greater detail and began to be put into practice. It’s no coincidence that we can still quote writers from the 1600s when we’re defending rationality itself.

With its mix of history and practical advice, this book is as close as you can get to taking Pinker’s class without attending Harvard.

The Foundations of Rationality

Discovering great ideas isn’t just about defending your own position. It’s about making an effort to prove yourself wrong. Pinker invokes Karl Popper’s line between science and pseudoscience to make that point:

“…most scientists today insist that the dividing line between science and pseudoscience is whether advocates of a hypothesis deliberately search for evidence that could falsify it and accept the hypothesis only if it survives.”

This is not how most people think about thinking. Defending your position is only half of what you need to do. Refining your idea so it can withstand challenge is a better way to go.

It also requires you to face hostile reactions to your opinions. It’s an unpleasant experience, but it’s far from life-threatening. As long as it’s not accompanied by physical danger, facing audiences and thinkers who disagree with you — even those whose thoughts are appalling — can refine your own opinions and uncover new ways to make old and important points.

Rationality Even Works for Morality

Rationality has a reputation for being cold and feelingless. However, rationality can be used to find the best ethics as well as it can make scientific progress.

(Popular fiction also began during the Enlightenment. The recognition that every person had a perspective regardless of their economic class created a demand for stories from new perspectives, even if many were excluded for reasons of race, religion, and ethnicity.)

The tools of rationality can even get us to the Golden Rule. Observing that you have things you like having done to you and recognizing that other people have inner experiences similar to your own is enough to get to “treat others as you want to be treated.”

Similar rules have popped up in different cultures across time, independent of each other as Pinker explains:

“Versions of these rules have been indepednetly discovered in Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Islam, Bahai, and other relgioins and moral codes. These include Spinoza’s observation, ‘Those who are govered by reason desire nothing for themeslves which they do not also desire for the rest of humankind.’ And Kant’s Categorical Imperative: ‘Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it shoudl become a universal law.”

Pinker also cites John Rawls and a common admonition to children: “How would you like it if he did that to you?”

Whether they’re problems common to humanity or niche intellectual challenges, Pinker shows how rationality is applied to find the best solutions to them.

What’s the Point of Rationality?

Rationality isn’t just about being smart. Pinker argues that working toward the best solutions is morally necessary. Irrationality can be unapologetically cruel.

Near the end of his book, Pinker cites a study by Tim Farley. Farley tried to estimate how dangerous irrationality was at scale. Pinker describes the study Farley undertook to answer that question:

“From 1970 through 2009, but mostly in the last decade in that range, he documented 368,379 people killed, more than 300,000 injured,, and $2.8 billion in economic damages from blunders in critical thinking. They include people killing themselves or their children by rejecting conventional medical treatments or using herbal, homeopathic, holistic, and other quack cures; mass suicides by members of apocalyptic cults; murders of withces, sorcerers, and the peopel they cursed; guileless victims bilked out of their savings by psychics, astrologers, and other charlatans; scofflaws and vigilantes arrested for acting on conspiratorial delusions; and economic panics from superstitions and false rumors.”

Farley also ran an X account called @Whatstheharm. It’s no longer active, but one of the gems is the homeopathic doctor who treated a four-year-old with saliva from a rabid dog.

Using irrational beliefs to chase a false solution can be harmful. Not every irrational belief is life-threatening. Crystal shops are harmless if no one’s replacing medicine with quartz necklaces.

However, irrationality is always a latent danger. Irrationality allows people to believe cruelty is kindness and misinterpret their harms as help.

Rationality is a great return to first principles about how to think. It’s a much-needed primer for anyone who wants to navigate the noisy and conspiracy-ridden online environment.