Lessons from the Askari: How Oppressive Regimes Endure

Discover what the askari story teaches about complicity, survival, and the mechanisms that sustain violent governments.

“Askari” may not be a term that many outside South Africa are familiar with, but it is a phenomenon that anyone interested in politics should understand.

The askari were black South Africans who worked with the apartheid state to assist operations against anti-apartheid activists, like Nelson Mandela and other members of the African National Congress (ANC). Members of South Africa’s state security services, like Eugene de Kock, led operations within and outside of South Africa to kidnap and assassinate South Africans who wanted equality under the law, regardless of race.

When de Kock spoke to one Askari about the remoteness of the farm the security services worked from in the 1980s, he said:

“‘This fence is not to keep you inside; it is to keep out the outside world.’ De Kock told Radebe he could run if he wanted to, but that he would have nowhere to go. The ANC would kill him for treachery; De Kock and his men would kill him for desertion. Many askaris stayed…Radebe declared, ‘In reality, we were hostages. We were captured…you take each day as it comes.’ He said many askaris decided to accept the police ‘offer’ to become collaborators in the hope that ‘at the right time I will run’.”

Askaris had made the choice to collaborate with the police, only to discover that they could never leave. Others joined the police out of fear. Others still didn’t want to be on the losing side of the anti-apartheid conflict.

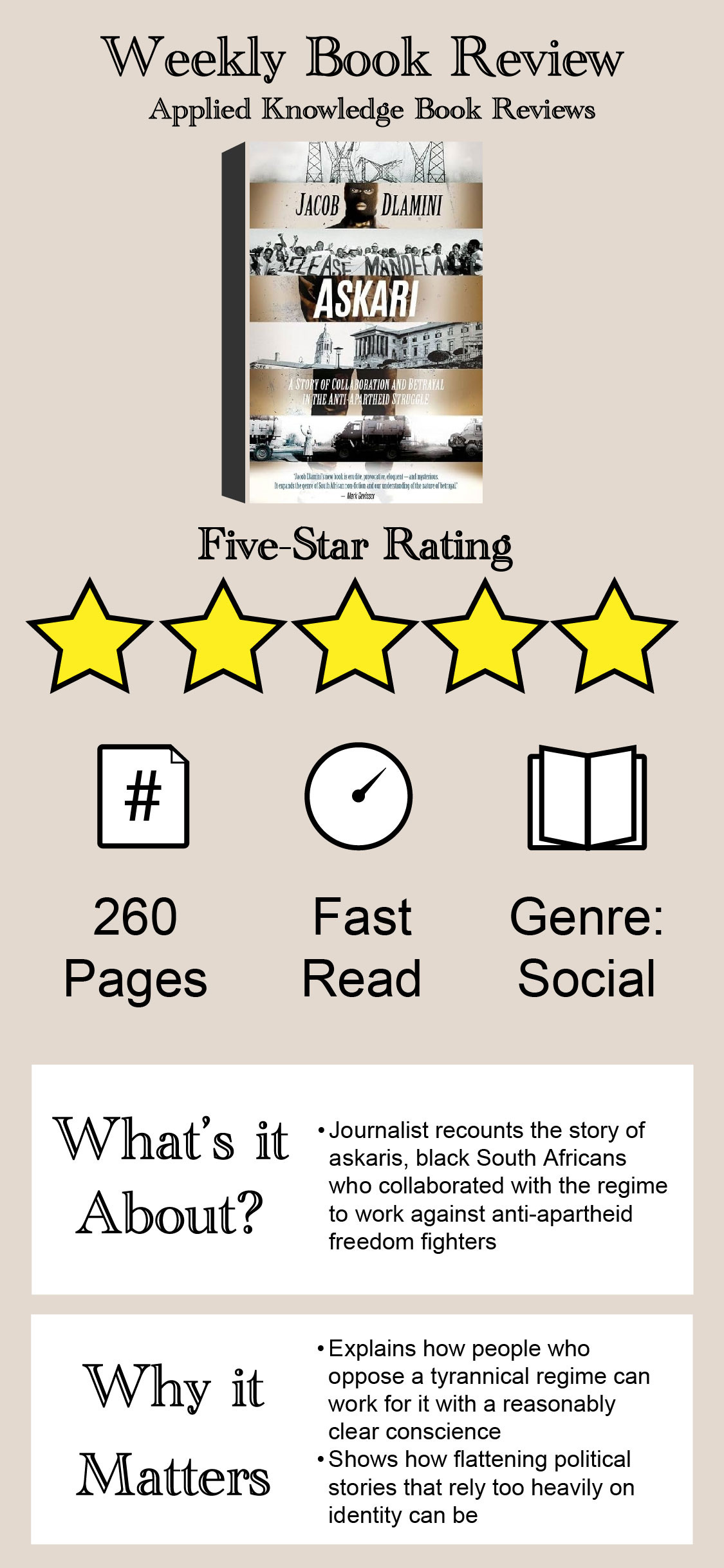

Whatever their reasons, askaris betrayed the anti-apartheid struggle and are crucial to understanding for anyone wondering how violent and oppressive governments can continue existing. Jacob Dlamini’s book Askari is a revealing answer to questions like these.

Why Would Askaris Turn on Their Countrymen?

It seems inconceivable that a black South African would work for the white government enforcing pass and employment laws. But police torture aside, doing seemingly trivial work like telling the police which teeth an anti-apartheid figure was missing didn’t seem like it would harm the cause. However, that is exactly the kind of work that made the police seem all-powerful, as a study of the East German Stasi demonstrates:

“The trivia about peole’s affairs, drinking problems and other minutiae that informers fed into the Stasi system mattered. ‘It was…precisely this sort of seemingly trivial and banal personal information which could be extremely useful to the Stasi. Such information could potentially be used to blackmail others, and it also helped construct a comprehensive personality profile of designated state enemies, which would facilitate the creation of plans to dispose of them.”

Imagine being kidnapped by the police and your interrogator knowing about your drinking history, missing tooth, and other intimate details of your life. It makes the state seem omnipotent and is a useful way to break the will of prisoners, even those fully committed to their cause.

However, Dlamini doesn’t conclude that dying for a cause is the right approach either. He points out a common problem with the way commentators often say that a dissident “chose” death instead of betraying their cause:

“While the proposition is driven by the noble sentiment that freedom is worth dying for, it minimises the culpability of her killers. To say Ndwandwe chose death is to suggest that her killers gave her what she wanted. It is to reduce her to a means for the ends of freedom. It throws the uniqueness of her life and her brave moral stance into the river Martyr, forever flowing with the blood of revolutionaries. More than that, it risks absolving her killers of their responsibility for her death.”

Why Aren’t Askaris Better Known?

During the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) work, several apartheid figures like Eugene de Kock became well-known names and faces. The TRC uncovered askaris throughout their hearings. Several of them had tense exchanges with commissioners who had been imprisoned and tortured by the apartheid regime.

However, few askaris are known at all, much less recognizable names like de Kock. There’s a twisted irony explaining the poorly-known phenomenon:

“Ironically, the fictions of racial solidarity that made askaris so potent as counterinsurgency under apartheid have shielded them from exposure in post-apartheid South Africa. Taking advantage of assumptions that blacks suffered similarly under apartheid, askaris have presented themselves as victims of circumstances or as ‘hostages’. Former ANC member Mzwakhe Ndlela has pointed out that ‘even those who were apolitical or reactionary started to identify themselves with the progressive forces. And so did some of those who had openly worked for the apartheid state. Everyone seemed to have a story to tell, placing themselves on the side of those who fought for freedom.”

The fictions that Dlamini refers to were stories that were deployed to explain South Africa’s politics. All black South Africans uniting against white South Africans who supported apartheid wasn’t completely untrue. Apartheid was a system of laws designed to ensure white superiority in South Africa. However, that story failed to explain how black South Africans could not only work for the police but also switch sides in the struggle altogether.

Askaris were complicated people who made the wrong decision to collaborate with the security forces. Understanding what turned them into traitors — and how easy many of them have gotten off in post-apartheid South Africa — tells readers in other countries how easily their political projects can be abandoned.