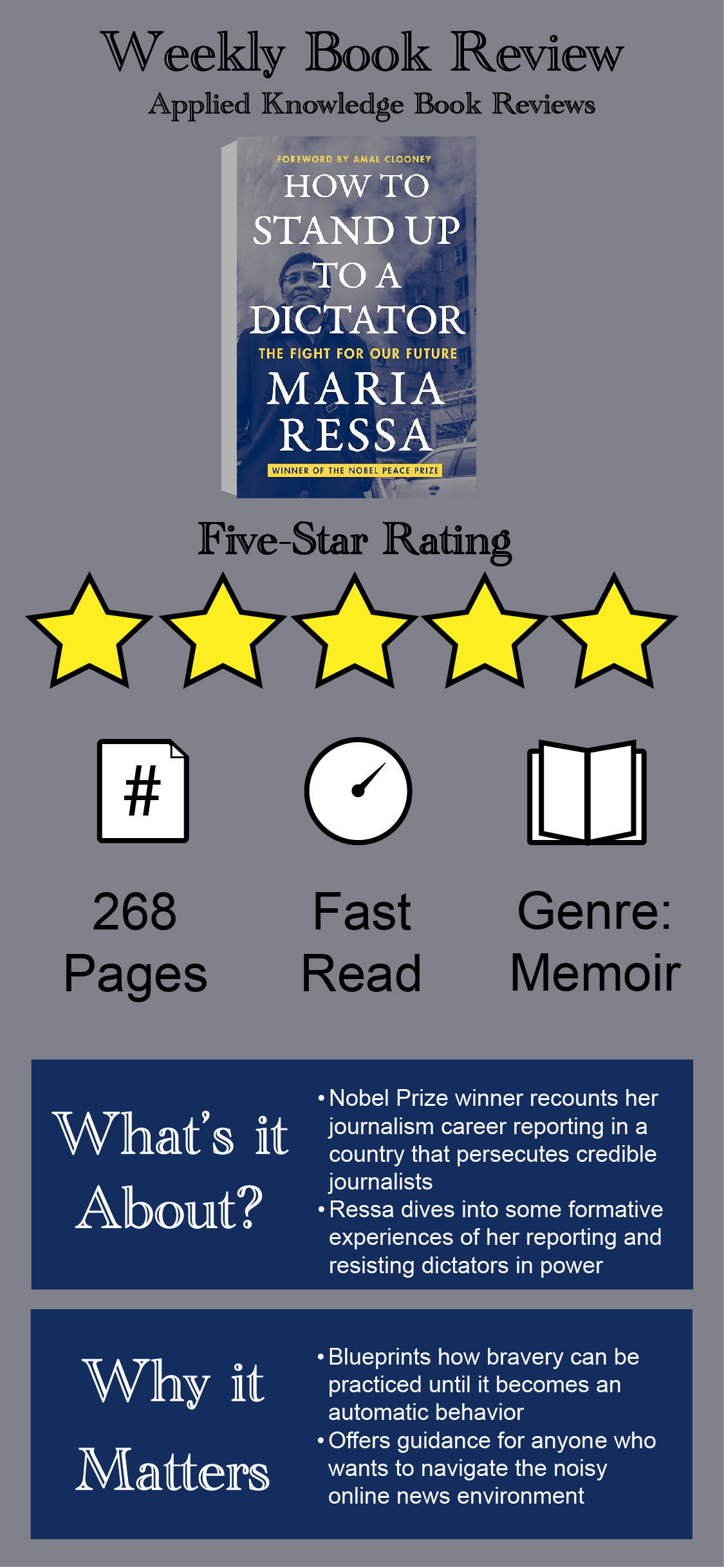

This Journalist Founded a Company to Stand up to a Dictator

Maria Ressa was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2021, one of two journalists to win the prize since 1935. This is her story.

One of the most striking things about Maria Ressa is her sense of purpose. She doesn’t make journalism sound like a job. Instead, she makes it sound like a calling that goes beyond platitudes about journalism’s relationship with democracy. Ressa embodies journalism at its best.

Her memoir, How to Stand Up to a Dictator, follows her life and career as a journalist in the Phillippines, but it also dives into deep questions about what journalism should be and what its role should be in a fucntional democracy. Readers will get deep dives into the problem of misinformation and its high-velocity spread online, especially on social media.

While it’s easy to speak about journalism as its best self, news outlets don’t always meet the standards that Ressa’s company, Rappler, has institutionalized.

The Power of Well-Run News Companies

Early in the section covering Rappler’s founding, Ressa recounts Phillipine president Gloria Arroyo. Shortly after Ressa got her job at ABS-CBN in 2007, the station learned that Arroyo “may have rigged the election” in 2004.

In 2006, Arroyo had already used a state of national emergency to restrict press freedom. She used raids, arrests, and the military to terrorize journalists and keep them from reporting information that could’ve harmed her tenure. Ressa writes:

“Arroyo was right to be afraid. ABS-CBN, in fact, could have been the spark that unseated her government. Soliders were actualy waiting for the media — for ABS-CBN specifically — to trigger their actions. We had a reporter with the elite Scout Rangers, and they told us they would march out into the streets the minute we showed them live on television. Through our reporter, I told them that we wouldn’t show them live until after they marched out. The line was clear in my mind: they must act first.”

It’s telling that Arroyo was so afriad of the free press. It had the power to give the people the information they needed to oust a president who cheated her way into office.

It’s also telling that Ressa’s press strategy was to record the government acting as the aggressor. If the government was going to physically attack one of her reporters, then the government had to be caught on camera in an instance of a campaign it was waging somewhat covertly. The harrassment of journalists wasn’t always in broad daylight, so it had to be documented to show people how the government exercised its “democratic” power.

The Arroyo episode was also an early lesson in Ressa’s career. She would go on to confront the arrests of fellow journalists and even more brutal arrests under later leaders. Practice makes it clear how Ressa confronted her corrupt government.

But it doesn’t tell us why she continued the fight.

Being Free by Example

Arroyo left office in 2010. In 2016, Rodrigo Duterte won the presidency with the help of two important companies: Facebook and Strategic Communication Laboratories, the parent company of Cambridge Analytica. Facebook collected data to build profiles that Cambridge Analytica sold to political campaigns to target voters.

Duterte used Cambridge Analytica’s data to great effect. After his election, Duterte continued using social media to spread disinformation about Ressa. Eventually, lies gave way to threats, and Ressa faced decades in prison on false charges.

But she never stopped fighting. Ressa continued running Rappler, the news organization she founded to use social media to crowdsource news and fight disinformation.

Near the end of her memoir, Ressa draws on an Ursula K. Le Guin quote to explain why she kept resisting. (She also swapped the sexes of the original quote since it’s describing her and not a male):

“You thought, as a girl, that a mage is one who can do anything. So I thought, once. So did we all. And the truth is that as a woman’s real power grows and her knowledge widens, ever the way she can follow grows narrower: until at last she chooses nothing, but does only and wholly what she must do.”

The more that Ressa learned about government abuse, the more she felt called to expose it. Resistence stopped being a choice and became her job.

It seems to be a common attitude among political dissidents. That quote could equally describe Alexey Navalny’s disregard for Putin’s threats, assassination attempts, and prolonged prison sentences throughout his life. He’d been resisting, exposing, and trolling the government for so long that he stopped choosing and just kept doing.

This is the attitude present throughout How to Stand Up to a Dictator, and the exploration of the conditions that led to that resilience makes the work a philosophical exploration of dissidence as much as a recounting of a couragous life.