How to Tell Real Skepticism from Lunacy

Skeptics make sure their beliefs are well-supported. That means embracing doubt instead of claiming to be without out.

One of the most common refrains from online commentary is someone defending unreasonable beliefs by saying they’re skeptics. Skepticism has a proud tradition of questioning widely accepted beliefs that haven’t been updated or properly interrogated.

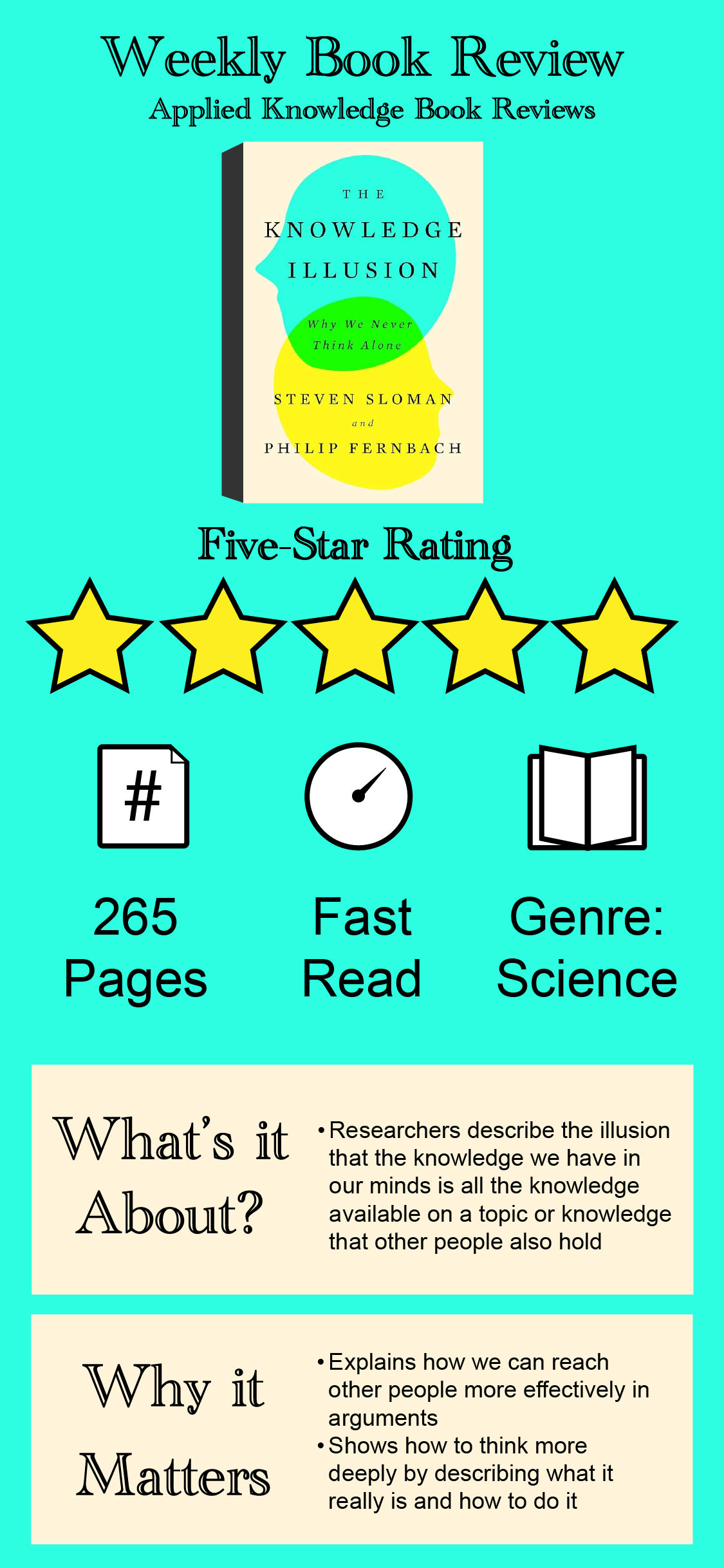

However, many people spreading misinformation fail to recognize that what they’re calling skepticism is really false confidence in the totality of their knowledge. The authors of The Knowledge Illusion describe the unearned confidence that comes from assuming the knowledge in your head is all the knowledge there is:

“Because we confuse the knowledge in our heads with the knowledge we have access to, we are largely unaware of how little we understand. We live with the belief that we understand more than we do. As we will explore in the rest of the book, many of society’s most pressing problems stem from this illusion.”

No single book can fix the polarization that individualized bubbles of information has wrought on civil society. However, this book’s findings show a clear path to practicing intellectual humility and recognizing it in others.

Changing Minds Can Take a Village

In our review of Daniel Dennett’s book on thinking tools, we introduced the idea that no one has one belief. Even the belief that everyone you meet is alive includes many other beliefs about what life, memory, and consciousness are. The Knowledge Illusion goes a step further to describe why people cling to beliefs that have long been disproven:

”…beliefs are deeply intertwined with other beliefs, share cultural values, and our identities. To discard a belief often means discarding a whole host of other beliefs, forsaking our communities, going against those we trust and love, and in short, challenging our identities…”

Trying to overwhelm someone with facts doesn’t change their mind. The person you’re arguing with is connected to a network of people whose esteem partially depends on your opponent believing the same things their community does. Your antagonist may tolerate eye rolls from you. They don’t want to take that from people whose respect they’ve worked hard to acquire.

Changing an entire community’s mind is even more unlikely than one stubborn person. However, there is a way to break through: focus on doubt instead of certainty.

What is Deep Thinking, Really?

Many people approach arguments based on what they know. The Knowledge Illusion suggests explaining how you came to your own beliefs. A study of climate change denial found that describing the mechanism of how climate change occured was more effective in making people question their beliefs than repeating facts about increased average temperatures. The authors explain:

”…it’s harder to dismiss the discovery that one doesn’t understand the mechanisms at play…The first step to correcting false beliefs is opening people’s minds to the idea that they and their community might have the science wrong. No one wants to be wrong.”

Doubt is a crowbar that creates space for new evidence. No one wants to feel like they’re completely wrong about how the world works, and showing the gaps in their knowledge can make them more likely to not just listen to but also consider new information.

Embracing doubt isn’t just for arguing with others. It’s an effective self-reflection tool as well. Recognizing what you don’t know is the key to deeper, more profound thought:

”Pondering your reasons for your position will do nothing but reinforce what you already believe. What you have to do is think about the issue on its own terms, think about exactly what policy you want to implement and what the direct consequences of that policy would be and what the consequences of those consequences would be in turn. You have to think more deeply about how things work than most people do.”