How to Productively Challenge What Others Think

Christopher Hitchens imparted a lot of wisdom in how to be a contrarian without falling for any conspiracy you cross paths with.

Christopher Hitchens is celebrated as a contrarian and debater. He’s also reviled for many of the same qualities.

Hitchens was a famous contrarian, someone who was willing to have an argument over any of his or his opponent’s beliefs in full public view, no less. He has a cult following that spans the atheist community to the online commentariat that admires his skillful debate and strong opinions.

(In his memoir, Hitchens admits that he has a tendency to double down on a position when challenged on it. It’s a trait he attributes to his father, and Hitchens regrets that tendency. His tendency to double down also makes him one of the most captivating debaters to watch, even if he should probably cede at least some ground.)

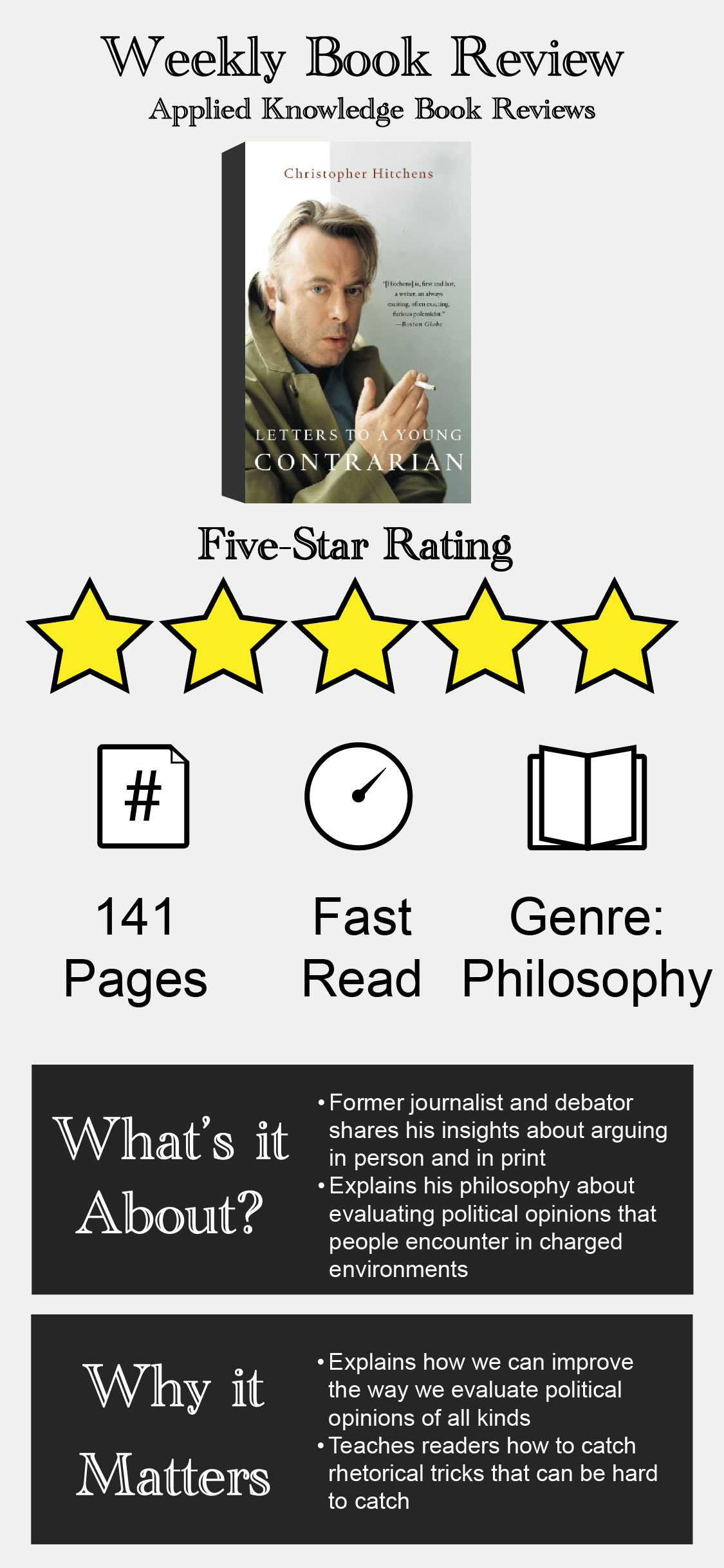

He wrote Letters to a Young Contrarian to explain his worldview and pass his skeptical attitude to the next generation of writers and thinkers. An early passage neatly summarizes Hitchens’ attitude toward thought and argument:

“There is a saying from Roman antiquity: Fiat justitia—ruat caelum. ‘Do justice, and let the skies fall.’ In every epoch, there have been those to argue that ‘greater’ goods, such as tribal solidarity or social cohesion, take precedence over the demands of justice. It is supposed to be an axiom of ‘Western’ civilisation that the individual, or the truth, may not be sacrificed to hypothetical benefits such as ‘order.’ But in point of fact, such immolations have been very common.”

How You Arrive at an Opinion Matters

One of the things that was unique about Hitchens was his willingness to change his mind in public. He publicly renounced communism, supported the war in Iraq to the consternation of his leftist allies, and attacked John le Carre over his defense of theocratic outrage at Salman Rushdie’s book, The Satantic Verses.

He was a lot.

But he knew how to take a position and stick to it until he was convinced to change his mind. His arguments with friends and ideological bedfellows are particularly instructive, as is his explanation of how to evaluate political ideas:

“In an average day, you may well be confronted with some species of bullying or bigotry, or some ill-phrased appeal to the general will, or some petty abuse of authority. If you have a political loyalty, you may be offered a shady reason for agreeing to a lie or a half-truth that serves some short-term purpose. Everybody devises tactics for getting through such moments; try behaving ‘as if’ they need not be tolerated and are not inevitable.”

That advice has aged especially well in our hyper-polarized world of social media and Trumpian politics. It’s tempting to accept an idea contrary to your values because your political tribe found a way to endorse it. Hitchens warned his readers about that political move ahead of time. He also had thoughts on people who believe they can side-step decisions about right and wrong:

“Remember that saying nothing is also a decision, and that the relativists and the ‘nonjudgmental’ have made up their minds just as much, if not as firmly.”

What is ‘Everybody’ Really Like?

One of Hitchens’ friends, Peter Schneider, was a novelist who wrote about life in Berlin. Schneider covered a story about a German family that sheltered Jews who had “violated the Nazi race laws by marrying Aryans.” Schneider expected his audience to celebrate ordinary Berliners chipping in to save Jews imperiled by the Nazis. Hitchens describes the actual reaction:

“Instead the reaction was a surly one. It took him some time to realise that by describing the brave and generous but low-level and unheroic conduct of so many citizens, he had undermined the moral alibi of many thousands more, whose long-standing excuse for their own inaction had been that, under such terror, no gesture of resistance had been possible.”

Many Germans who collaborated with Nazis or refused to help thier Jewish neighbors believed that everyone behaved similarly. However, the realization that other people had behaved the opposite way angered many readers. Many ordinary people comfort themselves by believing other people share their faults. Heroic tales can rebuke readers as much as they can inspire them. Still, Hitchens found a silver lining to this episode:

“This depressing discovery need not blind us to the true moral, which is that everybody can do something, and that the role of dissident is not, and should not be, a claim of membership in a communion of saints. In other words, the more fallible the mammal, the truer the example. This sometimes cheers me up.”

Ordinary people are flawed, but those flaws don’t prevent them from having moments of heroism. Letters to a Young Contrarian is full of insights like these and worth the read — especially if you disagree with him.