How to Actually Save Money and Other Psych Hacks

Behavioral psychologists are obsessed with finding ways to help us help ourselves, and this book is full of ways to do it.

It’s hard to save money or start a diet, even if you know you should. However, behavioral psychology has some hacks that can make it easier to take care of ourselves.

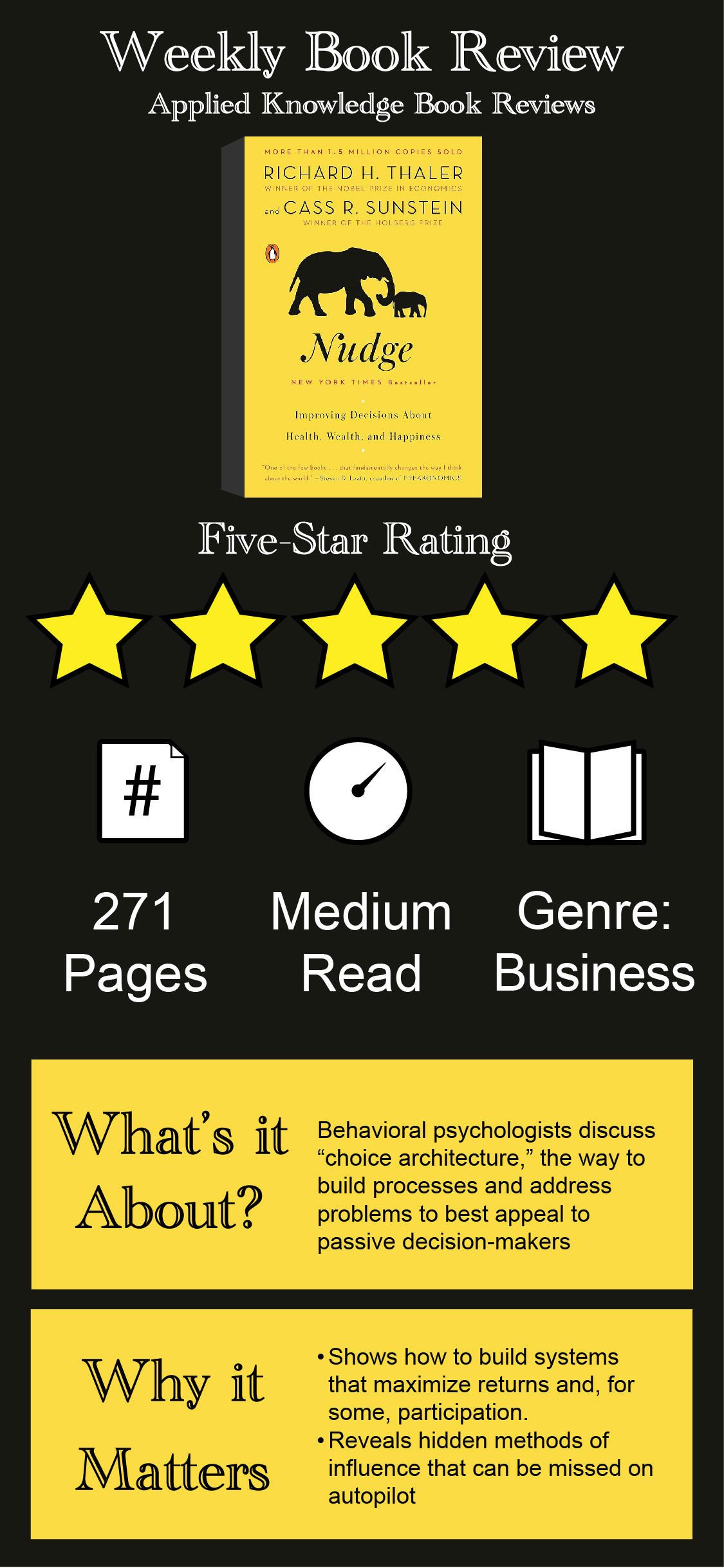

Nudge is a collection of those tips. Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein break down something they call choice architecture. They discuss ways to design programs to help people make better choices by default instead of having to commit to changing their behaviors.

While Predictably Irrational was about individuals, Nudge is about how people can design programs to make more people participate in them. Individuals still retain their ability to make their own choices. But little things like making people opt out of a program instead of into it improve retention rates — all because of psychological quirks we never think about.

Framing Makes All the Difference

Early in the book, the authors ask their readers to imagine they need an operation. If the doctor asked “Out of 100 patients, 90 are alive in five years,” many people would accept the operation. But if the doctor pitches the same procedure by saying 10 patients are dead in five years, fewer people would be willing to take the operation.

This is the power of framing. If something uncertain is framed in a positive way, then we're more likely to accept it than if it’s framed as a potential loss.

Credit card companies know this well. In the 1970s, Congress introduced a bill regulating whether retail merchants could charge different prices to their cash and credit card customers. Credit card companies didn’t want to lose revenue if retailers charged lower rates to credit card users. The authors explained how the credit card lobby tweaked the bill in their favor to hold onto higher rates:

“…the credit card lobby turned its attention to language. Its preference was that if a company charged different prices to cash and credit customers, the credit price should be considered the ‘normal’ (default) price and the cash price a discount — rather than the alternative of making the cash price the usual price and charging a surcharge to credit card customers.”

The credit card lobby ensured the default price would be the higher credit card rate. It relied on the passivity that many people make decisions with to secure higher revenue even after Congress regulated cash and credit card pricing.

“Nudges” aren’t all about passivity. They’re also about hidden cues that can be lifesaving.

Chicago’s White Stripes

Just after the credit card example, Nudge’s authors broke down a more practical example of a nudge.

Chicago has a long street called Lake Shore Drive that runs along Lake Michigan. One stretch of that road is “a series of S curves.” Chicago had trouble with drivers ignoring the speed limit reduction and wiping out on one of the turns. Clearly, speed limit signs weren’t cutting it. The authors described the white stripes painted on the roads that actually helped:

“When the stripes first appear, they are evenly spaced, but as drivers reach the most dangerous portion of the curve, the stripes get closer together, giving the sensation that driving speed is increasing…One’s natural instinct is to slow down.”

Instead of relying on drivers to do the right thing, Chicago designers changed the way drivers perceived the road.

Nudge isn’t about overruling people’s thoughts or preferences. It’s about taking advantage of how passively many people approach mundane decisions. Anyone who makes the effort to think about the substance of a choice can ignore nudges — probably see through them, too.

But if you’re someone who has to solve problems that involve large groups of people, Nudge may be a worthwhile read.