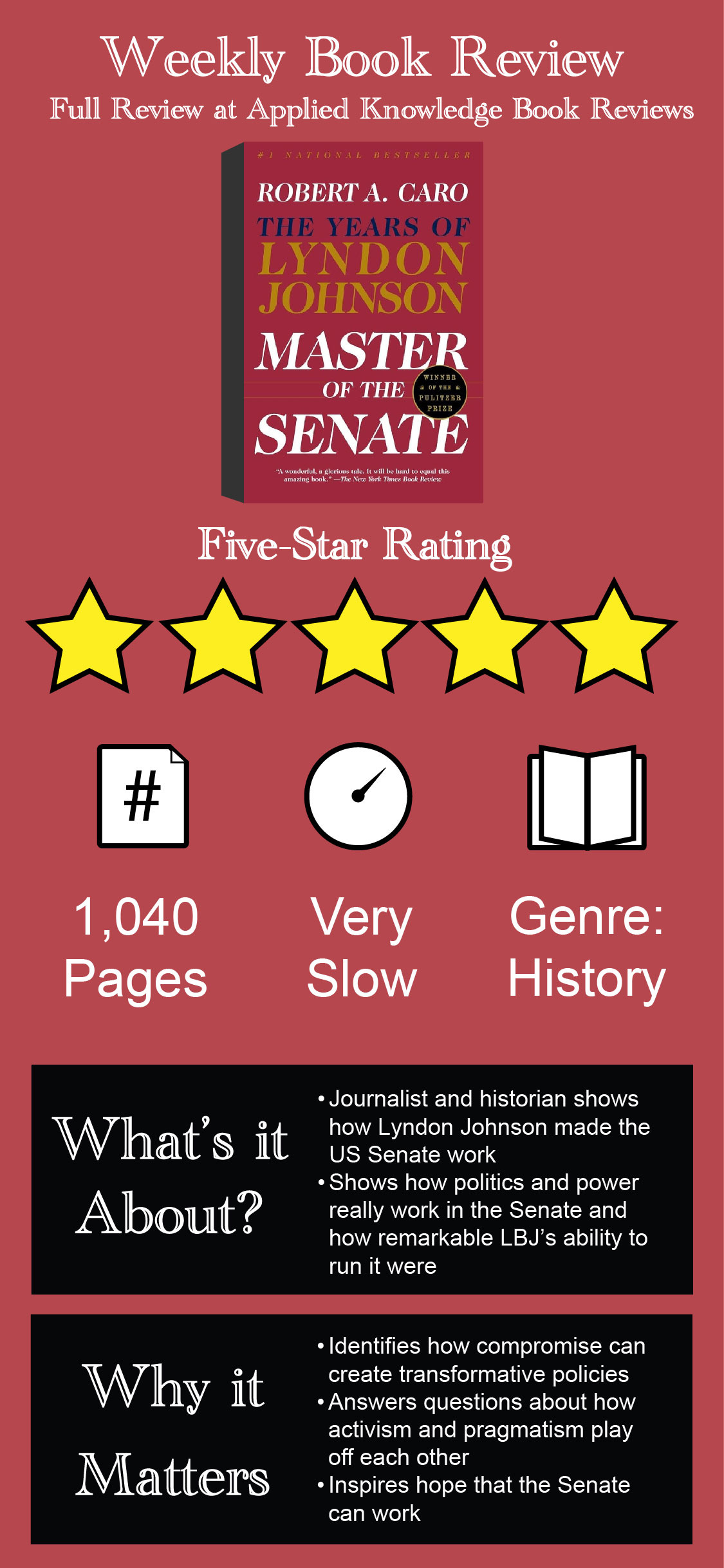

How LBJ Ran the Senate and Made it Work

The stories of Lyndon Johnson and the Senate show how government should and shouldn't work. Master of the Senate unravels these crucial, intertwined stories.

Congress doesn’t have a reputation for efficient work, but one man made it possible to pass a slew of bills, including the first Civil Rights bills since Reconstruction.

Master of the Senate is really two interwoven stories. Robert Caro details the history of the Senate and how it became dysfunctional. Caro also recounts Lyndon Johnson’s years as Senate Majority Leader. It’s a detailed tome that shows anyone how to acquire and exercise power, even in a suboptimal institution.

Johnson was built for congressional politics. His ability to inspire pity, fear, and admiration at will allowed him to make Southern Dixiecrats and Northeastern Liberals believe he was on their side. (His camouflage ability didn’t work on everyone. He spent his later Senate years dispelling liberal suspicions of his anti-civil rights voting record.)

The Senate isn’t thought of as an interesting or functional institution. However, the palace intrigue that goes into running it successfully and the unique character of Johnson make Master of the Senate a fascinating study of power acquisition and reform.

LBJ Made Acquiring and Exercising Power a Science

One of the first things that Caro describes is how badly Johnson wanted to be president. The presidency was in his sight since he was about 10, and his early political machinations in school taught him vital lessons that would apply even during his Senate and presidential years. He used them to rise meteorically to political power. Caro wrote:

“At twenty-one, while still an undergraduate at a little teacher’s college known as a “poor boys’ school,” he was running two campaigns, one for a state legislator, the other for a candidate for lieutenant governor, in a block of Hill Country counties, and politicians all over Texas began hearing about “this wonder kid” who “knew more about politics than anyone else in the area.”

Johnson also made a club of congressional age “influential” on Capitol Hill. By age twenty-six he became “perhaps the youngest person the New Deal ever put in charge of a statewide program” as the National Youth Administration’s director. He was a House member by twenty-eight but made a mistake in his first Senate bid in 1941. Johnson wouldn’t make it to the Senate until 1948.

By then, there were a few lessons he had to pass on to his aides.

Lessons in Power from LBJ

“If you do everything, you’ll win.” It was a mantra Johnson would repeat throughout his career, including his failed presidential bid against John Kennedy. Still, it was a reliable strategy. Johnson only experienced a handful of setbacks in his grabs for higher office.

His relentlessness was one of his most well-known traits. Caro writes:

“He could dominate a room with his charm. In his circle of young New Dealers in Washington, he was the life of every party with his practical jokes, quick wit, his wonderful “Texas stories” about the hellfire preachers and tough old sheriffs of the Hill Country, his vivid imitations of Washington figures, and his exuberance; jumping up on a table in a. Spanish restaurant, he pulled little Welly Hopkins up with him to dance a flamenco.”

Johnson was at his best when his force of personality and work ethic combined with a cause he adopted. If he signed onto a cause, he went all into it. As a child, “he had heard a salesman say,…“You’ve got to believe in what you’re selling.” The impact that quip had on him was profound as his attorney, Ed Clark, remembered:

“He [Johnson] was an emotional man, and he could start talking about something and convince himself it was right, and get all worked up, all worked up and emotional, and work all day and all night, and sacrifice, and say, ‘Follow me for the cause!’ - ‘Let’s do this because it’s right!’”

This was the force of personality that would push civil rights legislation through the Senate in 1957 and 1960. Johnson would also pass enforceable civil rights legislation as president in 1964 and 1965. Caro makes him as entertaining on paper as a real, flawed person.

How the Senate Works and Why it Doesn’t

The second story within Master of the Senate is the story of the Senate itself, and it’s illuminating. James Madison designed the Senate to keep fads from becoming legislation. Madison wrote that the Senate’s goals were “first to protect the people against their rulers; secondly to protect the people against the transient impressions into which they themselves might be led.”

While the Senate has blocked reactionary policies from becoming law, it has also blocked legislation that the American people have clamored for. Caro wrote:

“The Constitution’s Framers had given the Senate power to block legislation, to stand as the rampart against the exercise of popular and presidential will. This power was only a negative power, a naysaying power, the power to obstruct and thwart. But it was an immense power - and the Framers had built the rampart solid enough that it was standing, thick and strong, in the twentieth century as it had stood in the nineteenth century.”

The Senate used to also be a powerful voice in foreign policy, but the United States’ role in the world outgrew the Senate. Caro noted that the United States’ budget in 1946 “was three hundred times the size it had been in 1890.” The Executive branch had grown to match, with the State Department doing much of the new foreign policy work.

In contrast, the Senate had roughly the same sized staff as it did in 1890 and lacked the expertise on staff to perform its check on the Executive branch. That sounds technical, but the degradation of what was supposed to have been the home of the highest form of American debate has consequences.

Master of the Senate is a must-read for anyone who wants to understand why laws can get gummed up in Congress. However, Caro’s tome is also a must-read for anyone who wants to see some example of the Senate working and what it takes to move that ancient body to action on hard issues.