How Genes Reach into the Real World

Genes don't just affect our bodies. They also affect the world outside of it through genetic influence on individual behaviors.

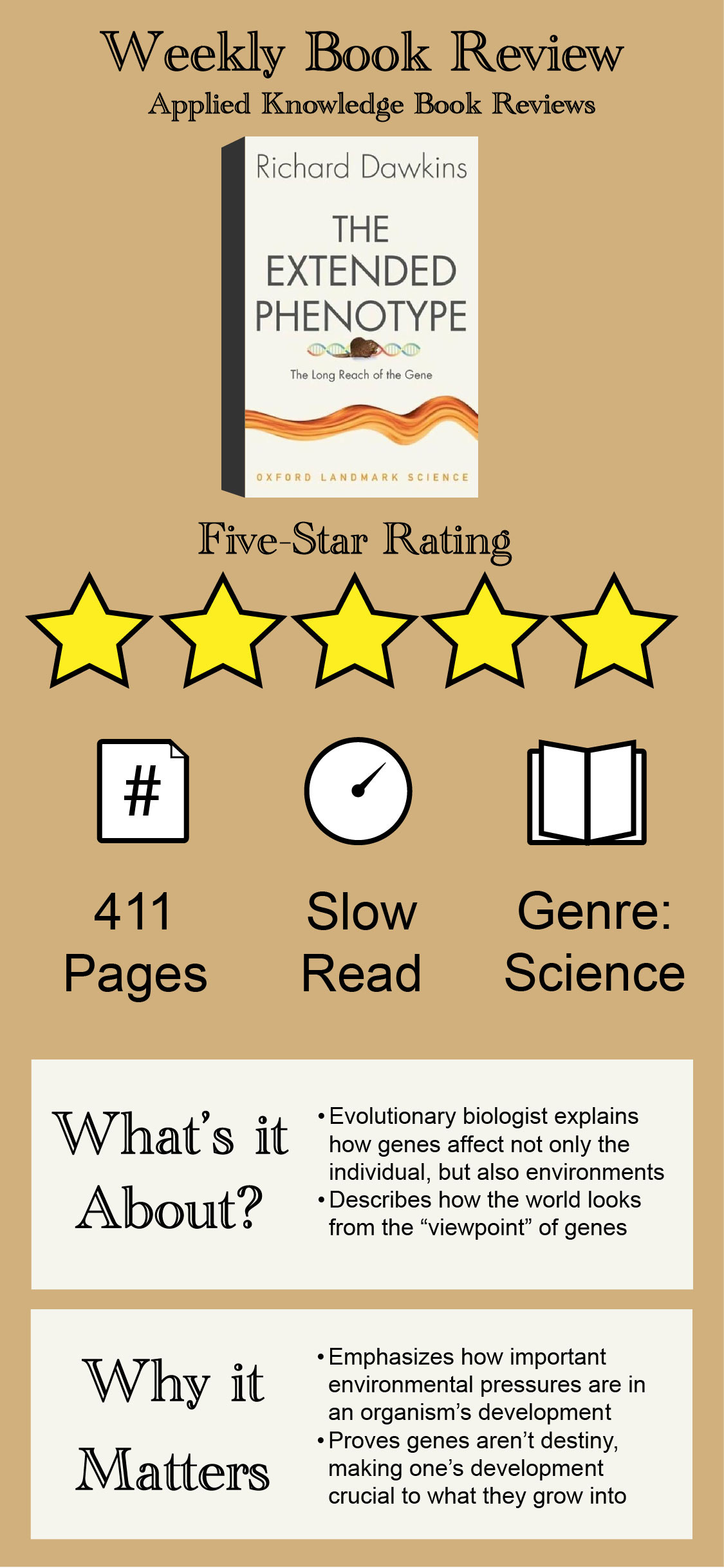

While he may be best known for The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins’ most impactful work may be The Extended Phenotype.

The physical expression of genes, phenotypes, affect how we look and influence how we behave. Dawkins’ previous work showed how individual bodies are a vehicle for genes. Genes are selected for their ability to be passed on to the next generation. The ones that express themselves are the ones that are best at ensuring they can be passed on.

The Extended Phenotype takes the logic of the gene’s eye view of life further to show how genes and their carriers manipulate the environment outside of bodies to ensure those genes make it to the next generation.

The Extended Phenotype

Dawkins lays a lot of groundwork to prove the extended phenotype theory. He states it succinctly about halfway through when he dives into the research behind the theory:

“The doctrine of the extended phenotype is that the phenotypic effect of a gene…is best seen as an effect upon the world at large, and only incidentally upon the individual organism — or any other vehicle — in which it happens to sit.”

After this description, Dawkins includes a chapter on using the extended phenotype theory in field research. He uses the case of a Sphex ichneumoneus — a wasp that burrows into the ground. Dawkins shows how looking at how often wasps burrow their own nests or invade others in a population of wasps.

Looking at what a group of organisms does shows the expression of genes that are being selected for. Rather than only looking at an individual to study genetics, biologists can look at population-wide patterns to study the selection pressures genes face.

Genes Aren’t Destiny

Central to the gene’s eye view of the world is the idea that genes aren’t destiny. It’s a point Dawkins makes very early in the book:

“Genetic causes and environmental causes are in principle no different from each other. Some influences of both types may be hard to reverse; others may be easy to reverse. Some may be usually hard to reverse but easy if the right agent is applied. The important point is that there is no general reason for expecting genetic influences to be any more irreversible than environmental ones.”

Genetics plays a crucial role in behavior, but there’s a nurturing piece that can decide which genes express themselves. Dawkins offers a dramatic example of “nurture” required to make certain groups of genes express their phenotypes:

“Female ants can sprout wings if they happen to be nurtured as queens, but if nurtured as workers they do not express their capacity to do so. More strikingly, the queens in many species use their wings only once, for their nuptial flight, and then take the drastic step of biting or breaking them off at the roots in preparation for the rest of their life underground.”

The Extended Phenotype is a fascinating study of the gene’s eye view of the world. Dawkins makes a technical subject accessible to any audience willing to grapple with his book’s details.

The book is also a comforting reminder that our genes don’t determine our future. The Extended Phenotype stresses how important our environment is to our development. It’s as true for queen ants and burrowing wasps as it is for us.