How Foxes Outthink Hedgehogs in a Complicated World

In a world with so many moving parts, thinking like a fox instead of a hedgehog can make sense of all the madness.

The world has too many moving parts for any person to keep track of. On the one hand, that complexity makes it impossible for a single organization to control the world. That should ease fears of the Illuminati and the lizard people they conspire with.

On the other hand, it makes every self-proclaimed prophet wrong by default. No savior can perfectly rule the world and no prophet can perfectly see the future. Anyone who wants to understand the world has to take in many moving parts at once and be ready to change their understanding of how the world works on a dime.

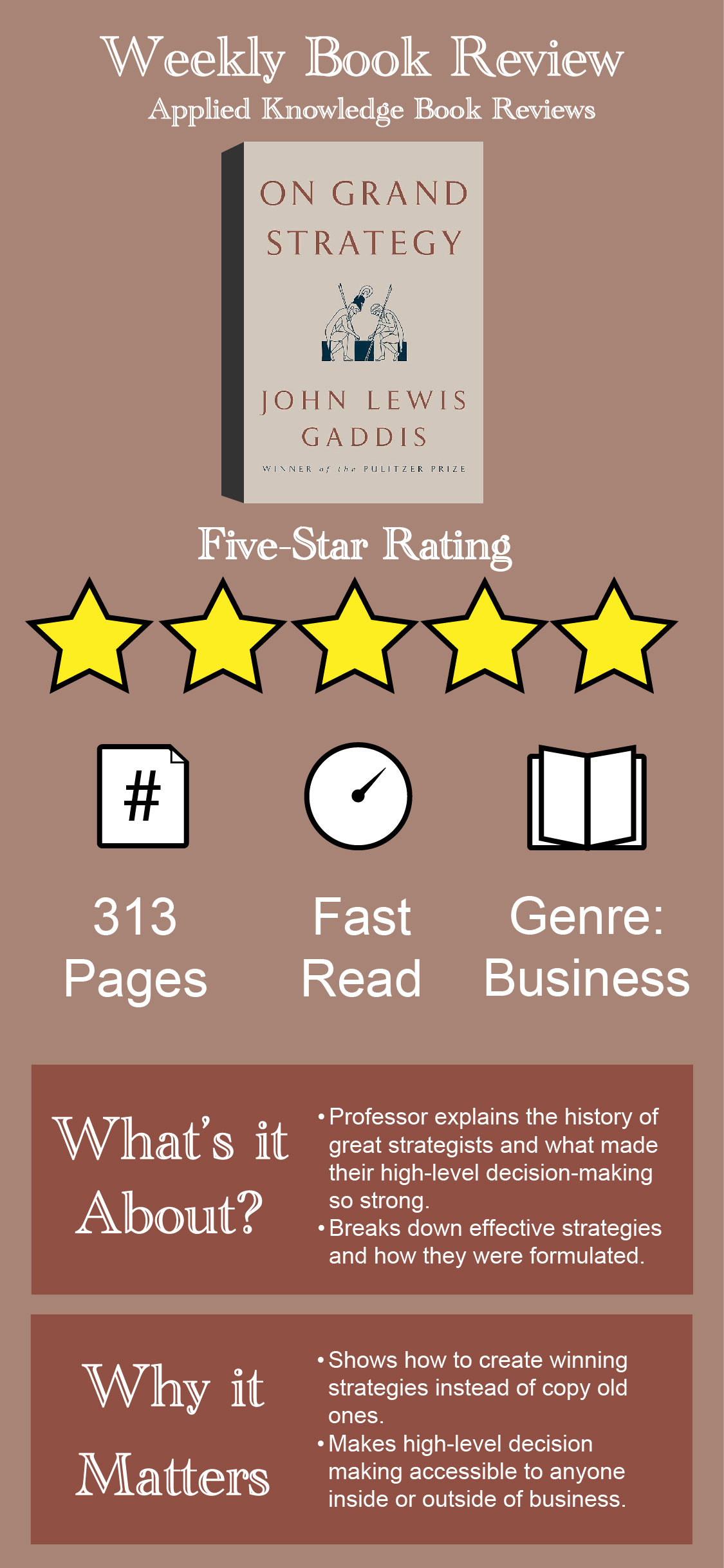

John Lewis Gaddis begins On Grand Strategy by making a similar argument. Gaddis draws on great tacticians throughout history to understand great strategic thinking. It’s a must-read for anyone in business, but it’s also valuable to anyone who’s trying to navigate the digital news landscape.

Hedgehogs are Popular. Foxes are Right.

Gaddis began by exploring the type of thinker that did the best job of predicting the future. He drew from Philip Tetlokc’s study of political predictions from two different types of thinkers: hedgehogs and foxes.

“The results were unequivocal: foxes were far more proficient predictors than hedgehogs, whose record approximated that of a dart-throwing (and presumably computer-simulated) chimpanzee,” Gaddis wrote.

The hedgehogs were wrong because they “brushed aside criticism” and “aggressively deploy[ed] big explanations.” They leaned on large patterns to single-handedly explain complex political events.

In contrast, foxes drew from many disciplines, recognizing that politics had too many variables to reduce to predictions with simple rules. Foxes’ improved predictive ability doesn’t make them popular though. Gaddis explained:

“…they tended to be too discursive — too inclined to qualify their claims — to hold an audience. Talk show hosts rarely invited them back. Policy makers found themselves too busy to listen.”

The hedgehogs’ “sound bits” were inaccurate but easier to digest and played better with audiences. Many audiences mistook hedgehogs’ false confidence and simple explanations for credible predictions.

Hedgehogs and Foxes Thrive in Different Environments

Hedgehogs are great showmen. They can boil complicated topics down to simple explanations and make themselves look like prophets.

But foxes have the ingredients to thrive in the real world. Gaddis quotes a passage from Tetlock’s study to explain where these two types of thinkers perform best:

“Foxes were better equipped to survive in rapidly changing environments in which those who abandoned bad ideas quickly held the advantage. Hedgehogs were better equipped to survive in static environments that rewarded persisting with tried-and-true formulas. Our species — homo sapiens — is better off for having both temperaments.”

Gaddis noticed something important from Tetlock’s study. Tetlock’s experts identified as foxes or hedgehogs. There weren’t experts who saw themselves as freak hybrids of both animals. That means we’re bad at switching between rule-following and rule-breaking. We lack flexibility.

That common failure has been identified by great strategic thinkers throughout history.

Theory is a Starting Point, Not an Ironclad Rule

Carl von Clausewitz was a great Prussian general who wrote On War. It’s a classic study of war and military strategy. Gaddis identifies one of the key takeaways from Clausewitz’s work:

“He places theory within the category of rules to which there can be exceptions, not laws that allow none. He values theory as an antidote to anecdotes: as a compression of the past transmitting experience, while making minimal claims about the future. he relies on theory for training, not as a navigational chart for the unseen.”

Theories are great at distilling patterns in the past into useful advice today. However, anyone who applies theory must understand why they worked in the past and what might be different about the present. Naval strategies that worked against 18th-century warships had to adjust to German U-boats in the 20th century.

The same principle applies in business. Understanding how giants like Apple or General Electric transformed and dominated their industries is important for any new founder or current executive.

However, founders should learn how Jack Welch and Steve Jobs identified gaps in their industries and weaknesses in their companies, not just try copying the actions those leaders took.

Not everyone can be a brilliant general or monopolize an American market. However, anyone can improve their information intake. Anyone can get better at learning how great strategists align their resources with their goals.