Catherine the Great's Complicated Legacy

Catherine the Great was an Enlightenment thinker, but she was also a monarch threatened by the budding democracy movement.

One of the most astonishing things about Catherine the Great’s rise to power was that it was made possible by a man unrelated to her who never imagined her.

In 1722, Peter the Great issued a decree abolishing male primogeniture. His decree allowed every Russian ruler to name their successor. Peter the Great made his second wife, Catherine I, empress after his death.

Thirty years later, another Catherine would ascend to the throne. She would also become the next “Great.”

A German by birth, she was married to Peter III. She was married off to Peter III about twenty years before he took the throne. He only ruled from January to July 1762. Catherine was a quick study of power and a voracious intellect. She overthrew Peter III when she realized how much better she could wield power than her husband.

In power, she proposed grand changes to Russia’s laws. Her most sweeping attempt was her Nakaz, an updating of Russia’s laws that would’ve established the rule of law and expressed disapproval of the death penalty. The ideas she expressed in this document drew from the French Enlightenment. She corresponded with Voltaire throughout her writing of the Nakaz and quoted several Enlightenment thinkers throughout her work.

However, she also repressed printers and radical thinkers in Russia when her power was threatened. After the murderous results of the French Revolution, Catherine the Great reversed her Enlightenment policies so abruptly that Voltaire wrote to her in anger.

Robert Massie captured this complicated titan in Catherine the Great. Her humor comes to life, and her correspondence with Enlightenment thinkers reveals the lengths she went to to modernize Russia, in culture, law, and science.

Above all, her intellect sparkles on every page.

A Reverence for Intellect — and Contempt for Idiocy

Among Catherine’s earliest influences were her teachers. The sense of independence that would dethrone her husband came from her studies and reverence for knowledge. Early in the book, Massie quotes a letter that Catherine would write to a friend in 1776:

“One cannot always know what children are thinking. Children are hard to understand, especially when careful training has accustomed them to obedience and experience has made them cautious in conversation with their teachers. Will you not draw from that the fine maxim that one should not scold children too much but should make them trustful, so that they will not conceal their stupidities from us?”

Her insistence that ignorance be made public so it may be dealt with is the spirit of the Enlightenment come to life. No longer did the great thinkers of Europe allow churches to set the boundaries of acceptable thought. Artists and scientists could push those boundaries, though the Church would push back.

Catherine’s Enlightenment inspiration is best seen in her Nakaz, her attempt to bring a more humane approach to Russian law.

A Flawed but Noble Rewrite of the Law

Catherine the Great’s passion for Enlightenment ideas was not shared by Russian elites. They enjoyed the power of life and death over their serfs. Long traditions of honor weren’t going to be uprooted overnight. That didn’t stop Catherine from trying to adjust the laws to fit her comparatively humanitarian vision. One of the passages from her Nakaz, instruction on new legal systems, read:

“The laws ought to be so framed as to secure the safety of every citizen as much as possible….Political liberty does not consist in the notion that a man may do whatever he pleases; liberty is the right to do whatsoever the laws allow….The equality of the citizens consists in that they should all be subject to the same laws.”

Equality before the law was a new concept. Russian elites could bribe their way out of trouble. Serfs would never get a hearing from anyone in imperial Russia’s legal system. They lived and died at the whim of their wealthier counterparts.

Catherine also took a view of torture that anticipated modern arguments against torture:

“The sensation of pain may rise to such a height, that it will leave him no longer the liberty of producing any proper act of will, except what at that very instant he believes may release him from that pain. In such an extremity, even an innocent person will cry out, ‘Guilty!’ provided they cease to torture him…. Then the judges will be uncertain whether they have an innocent or a guilty person before them. The rack, therefore, is a sure method of condemning an innocent person whose constitution is weak, and of acquitting the guilty who depends upon his bodily strength.”

For all its modern content, there’s one important thing the Nakaz doesn’t do. Catherine the Great does not embrace democracy. She maintained her belief in benevolent autocracy. Her concerns about the line between democracy and mob rule grew after the French Revolution.

Two Revolutions, One Great Step Backwards

The American Revolution was a bottom-up revolution that was supported by ordinary Americans. The Founding Fathers were in touch with the wishes of their people.

The French Revolution was the opposite. The revolutionaries imposed their vision of a free France onto their people. Anyone who offered a different vision was imprisoned or killed. The most infamous radical, Maximilien Robespierre, was killed by the guillotine himself at the end of the French Revolution. But the pile of French elites who were killed by Robespierre’s forces had grown alarmingly high in the years it took for the movement to turn on its founder.

Catherine wanted a more humane Russia. She wanted Russia to become the cultural center that France was, a country that could produce works of art that would excite intellectuals across the world. In her eyes, Russia could become a global center of scientific progress akin to Western Europe in the Enlightenment or the Islamic World in the Middle Ages.

However, she didn’t want any of those things at the expense of her life. Massie wrote:

“More than any other European monarch, she felt that the ideology of radical France was also directed at her, and the more radical France became, the more defensive and reactionary were her responses. She now discovered dangers in Enlightenment philosophy. Some responsibility for the excesses of the revolution seemed traceable to the writings of philosophers she had admired.”

The French Revolution began in 1789. By 1791, Catherine the Great “ordered all bookshops to register with the Academy of Sciences their catalogs of available books that were opposed to ‘religion, decency, and ourselves.’” The positive example of American democracy didn’t assuage her fears about the much closer French Revolution. Suddenly doubting the ideas she’d held dear for decades, Catherine the Great embraced traditional monarchical powers.

This is the complicated legacy of Catherine the Great. She anticipated both modern arguments we make against torture and the death penalty today. She also anticipated Cuba’s Decree 349, passed in 2018 requiring artists to register with the Ministry of Culture.

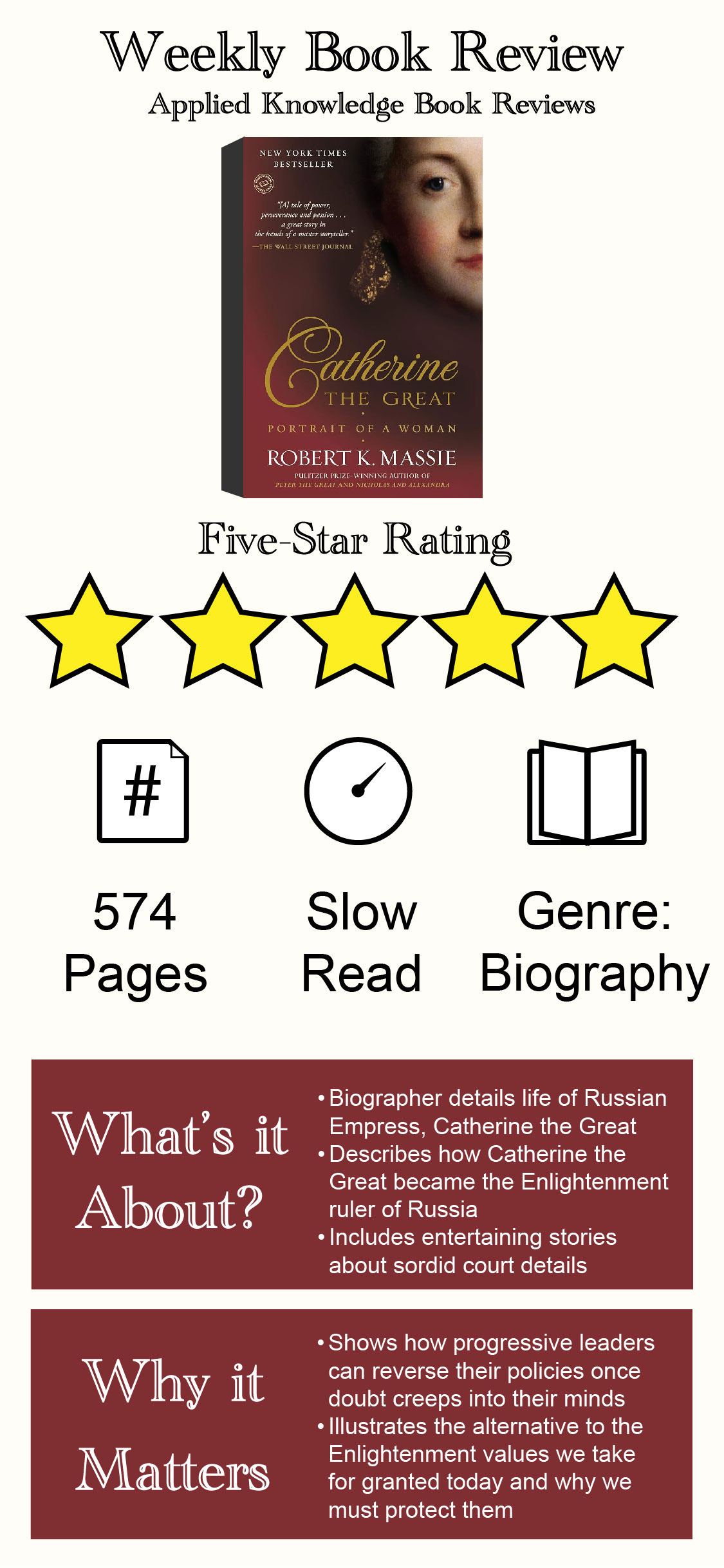

Catherine’s full complexity — as well as outlandish tales from her court — are available in this readable and thrilling biography of this modern and regressive titan of history. Massie’s account of her life is worth the time it takes to read it.